There’s a long history of Jewish people trying to recover art and family heirlooms taken from them during the Holocaust — which is what might have happened to a piece of art seized from the Carnegie Museum of Art in Oakland this week.

The artwork is believed to have been stolen during the Holocaust from a Jewish art collector and entertainer, according to the Associated Press.

“A lot of art was looted by the Nazis in the Holocaust,” Adam Hertzman, director of marketing for the Jewish Federation of Greater Pittsburgh, told the Tribune-Review on Friday. “It may have appeared to have been legally transferred, but that transfer was done under duress.”

Hertzman said he could not speak specifically about the case concerning the artwork at the Carnegie Museum of Art, but he said there has been difficulty around provenance art. That is documentation that proves the authenticity of a piece of artwork. Without provenance, there isn’t proper proof of who owns it and its value.

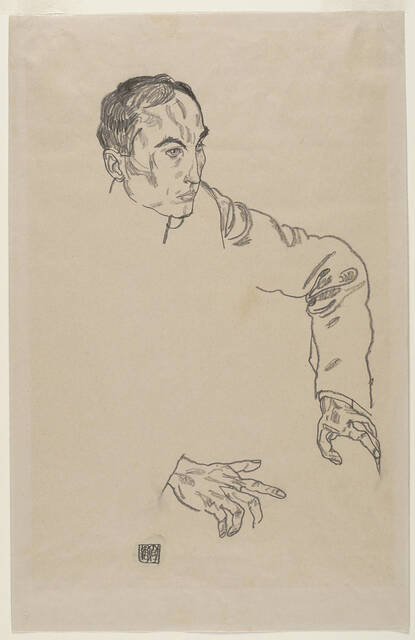

The piece in question is called “Portrait of a Man,” a pencil-on-paper drawing dated 1917 by Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele. It was seized Wednesday from the Carnegie Museum of Art by New York law enforcement.

“Portrait of a Man” is valued at $1 million. The work was previously owned by Fritz Grünbaum, a cabaret performer and songwriter who died at the Dachau concentration camp in 1941.

The museum issued a statement through TJ White, the managing director and head of special situations for Sloane & Company in New York City. The statement read, “Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh is deeply committed to our mission of preserving the resources of art and science by acting in accordance with ethical, legal and professional requirements and norms. We will of course cooperate fully with inquiries from the relevant authorities.”

When contacted by the Tribune-Review, White declined further comment.

“Unfortunately, I won’t be in a position to comment further outside of the previously provided statement,” he said via email.

Hertzman said the museum’s statement is heartening to him and others in the Jewish community.

“The museum’s desire to make it right and do the right thing shows they care about the preservation of art and its history,” Hertzman said. “The Nazis purposely rounded up what they called ‘undesirables’ and auctioned off all their stuff. It is hard to understand the magnitude of this.”

He said Nazis kept meticulous records. To many people, the Holocaust feels like an event that happened a long time ago, but Hertzman said he knows and is friends with children and grandchildren of people who survived and others who perished in the Holocaust.

“The pain and lingering effects of the Holocaust are still being felt today,” Hertzman said.

Barbara McCloskey is a professor at the University of Pittsburgh who teaches Art in the Third Reich and Memorializations of the Holocaust. The course examines national socialist art and the fate of modernism under Hitler in the years between 1933 and 1945.

She said in situations where you have a seizure of artwork, it is a way to right a wrong and return property to the rightful owner or heirs.

McCloskey said she doesn’t know the details of this situation but that there must be strong evidence to warrant the removal of the piece. She said she could not say whether there would be a penalty to the museum.

“Every case is different,” she said. ”You have to find out how the piece of art arrived at the museum.”

McCloskey said, from her research, a lot of property that belonged to Jewish people was sold to bring money into the Nazi regime. She said Schiele was an important artist.

There are many cases like this, she said.

“The U.S. and other countries have been actively working to find out what happened to stolen property and doing the right thing to find it and get it back to its owner or an heir of the owner,” she said. “This work has been going on for a long time. This art has monetary value, but it also is part of this person’s identity and culture.”

Friday marked the beginning of Rosh Hashanah, a high holy day for the Jewish community.

A warrant issued by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s office said there’s reasonable cause to believe this piece and two others are stolen property. The other pieces seized by Bragg’s office are “Russian War Prisoner,” a watercolor and pencil on paper piece valued at $1.25 million from the Art Institute of Chicago; and “Girl With Black Hair,” a watercolor and pencil on paper work valued at $1.5 million from Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College in Ohio.

The three works along with several others, which Grünbaum began assembling in the 1920s, are already the subject of civil litigation on behalf of his heirs. They believe the entertainer was forced to cede ownership of his artworks under duress.

Manhattan prosecutors believe they have jurisdiction in all of the cases because the artworks were bought and sold by Manhattan art dealers at some point.

The Associated Press contributed to this story.