Part 2 of 2 in a Richland History Group series about Lafayette’s role in helping America create its democracy during the Revolutionary War and chronicling the Western Pennsylvania Portion of his 16-month tour of America.

On May 30, 1825, American Revolutionary War General Marquis de Lafayette, his son Georges Washington de Lafayette, and their entourage arrived in Pittsburgh as part of a 16-month USA tour. The distinguished 67-year-old Frenchmen sat in a barouche carriage pulled by four white horses and waved to admiring citizens who crowded Pittsburgh’s streets.

Mayor John Snowden greeted him, and his carriage proceeded along Penn Avenue to Wood Street, where it stopped at the Darlington Hotel, the entourage’s residence while in Pittsburgh. For two days, the city was in a state of celebration. The traveling group had to move quickly after the Pittsburgh visit to stay on a very tight schedule requiring “The Nation’s Guest’s” presence in Boston on June 17 for a dedication ceremony honoring the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill.

On the morning of June 1, 1825, Lafayette departed Pittsburgh on the stagecoach that made regularly scheduled trips north to Bakerstown, Butler and ultimately Erie. Pittsburgh City Light Troops of Calvery served as escorts out of downtown Pittsburgh for this coach as it proceeded across Federal Street over the Allegheny Bridge (then covered) to the Pittsburgh-Butler Turnpike (roughly along the Route 28 corridor to Etna and then more or less continuing north along today’s Route 8).

The party stopped briefly near the mouth of Pine Creek at Buffington’s Tavern (Millvale/Etna area) to water their horses and have a brief ceremony with a trumpet played. Lafayette’s coach and the entourage then continued north toward Butler.

The Lafayette party moved very quickly on the Pittsburgh-Butler Turnpike, which passed through “downtown” Bakerstown on what is Heckert Road today. John McMeekin mentions this historic event in his 1951 “Richland USA.”

The authors of this piece presume that some Bakerstown (1825 Deer Township) and surrounding Richland (1825 Pine Township) area farming families stood in Bakerstown on each side of the dirt Butler Turnpike. They would have cheered and likely waived American flags as Lafayette passed. The coach was likely slowed down, allowing all to see Lafayette smiling and waving back.

Richland History Group research reveals that the following admirers could have been on the Turnpike cheering: William Waddle, Thomas Baker, John Crawford, Thomas Gibson, Issac Grubbs, John Dickey, John Ewalt, James Harbison, Charles Gibson and Mr. Gundaker. For three research reasons, we believe that there was no official ceremony in Bakerstown and that Lafayette may not have even stopped (if he did stop, it was ever so briefly).

One: He was in a hurry to reach Butler for planned ceremonies there. Two: Bakerstown was still quit small and sparsely settled (the 1825 population would have been less than the 130 recorded for 1830), unlike much larger 1825 Pittsburgh and Butler. Three: We have found no written record of any Bakerstown ceremony when Lafayette passed through. Upon leaving Bakerstown, Layafyette continued north on the Butler Turnpike at a very brisk pace.

Lafayette met a contingent from Butler about seven miles south of that town at “Mr. Lyons,” a dwelling located along what is now Route 8 (near Lakeview North Golf Course). Included in the contingent was an official from the Butler Turnpike, the road on which Lafayette was traveling. The group arrived in downtown Butler by mid-afternoon, meaning it made the Pittsburgh to Butler journey in considerably less than the normal 14 hours.

Lafayette was met by some 400 citizens who formed a procession lining the bridge at the town’s entry. This throng followed Lafayette’s coach. Three arches had been erected, each with a 24-star American flag and sign saying “Welcome Lafayette.” A brief parade and ceremony were held.

Former U. S. Senator Walter Lowrie welcomed Lafayette, who proceeded to the red brick Mechling’s Inn (also called the Mansion House) on West Diamond Street for a dinner served on French china, which is displayed today in Butler’s Lafayette Building.

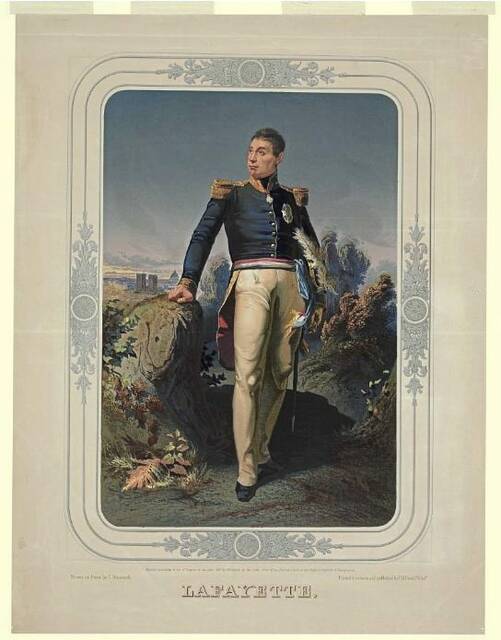

In 1894, Thomas Mechling recalled that Lafayette wore a “blue coat with white vest and buff colored nankeen pants.” He “ate freely of boiled sauerkraut,” according to the 1825 Butler Sentinel. “The National’s Guest” met with soldiers he served with at the Battle of Brandywine. At 4 p.m., after only a few hours in Butler, Lafayette and his group departed on a seven-hour journey to Mercer, named for Lafayette’s fellow Revolutionary War General and friend, Hugh Mercer. His parting words in Butler were “Farwell, my friends. You will not see me again.”

Few realize that the statement “all men are created equal,” the heart of the American Declaration of Independence, was a revolutionary idea in 1776. Lafayette, a constant advocate for freedom and democracy, not only embraced this new ideal but risked his fortune, freedom and life pursuing it. He made a call to end slavery long before the abolitionist movement took hold in America. Lafayette’s honorable legacy is rightly kept through the names of various U.S. cities, towns, streets, parks and landmarks. For a few moments almost 200 years ago, today’s Richland Township gave safe passage to this historic figure.