Thousands of visitors seek out Fallingwater and Polymath Park in Southwestern Pennsylvania each year to marvel at the works of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Why is there such inspiration in this area? Having a wealthy client and patron in Edgar Kaufmann certainly didn’t hurt. And as it turns out, the greater Pittsburgh region’s landscape is very much reminiscent of Lloyd Wright’s home environment in the rolling hills of Wisconsin’s Driftless region.

“It’s all steep hills and valleys,” said Stuart Graff, recently retired president and CEO for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. “Southwestern Pennsylvania is remarkably similar, with these lovely gorges and valleys.”

And while Fallingwater is impressive, an exhibit at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., takes a look at what might have been, exploring several unrealized projects Wright designed for the region between the 1930s and ’50s, and examining how his vision of the future may have impacted urban, suburban and rural landscapes.

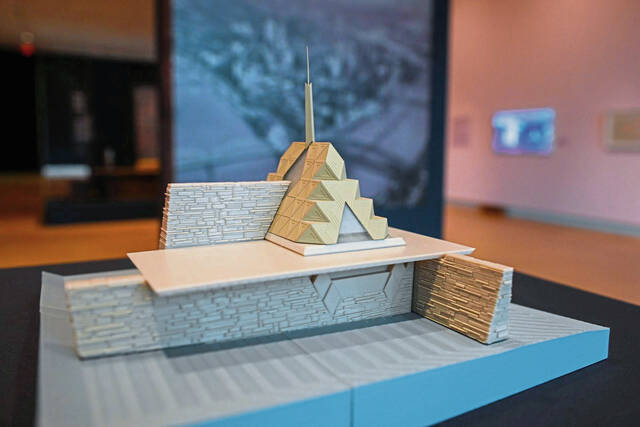

More than that, animated films created by Oklahoma-based Skyline Ink Animators + Illustrators allow museum visitors to virtually explore unrealized projects. They include a monumental re-imagining of the Point (1947), a self-service garage for the Kaufmann’s Department Store (1949), a gate lodge for the Fallingwater grounds (1941), and two designs created in 1952: the Point View residences, designed for the Edgar J. Kaufmann Charitable Trust, on Mount Washington and the Rhododendron Chapel at Fallingwater.

“Wright was always inspired by landscape,” Graff said. “He looked at this Pennsylvania landscape that was familiar to him and began thinking, ‘How can we work with this landscape to make the quality of people’s lives better? How do we take the natural vistas into account?’ ”

The exhibit was co-organized by The Westmoreland Museum of American Art and Fallingwater, a property entrusted to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. Scott Perkins, Fallingwater senior director of preservation and collections, said the two museums were interested in exploring the potential influence and legacy the structures would have had if they were built.

“We were sort of thinking, if they had built these — the civic center, the garage, the apartment tower on Mt. Washington — what impact would that have left on the city?” he said when the exhibit was on display in Greensburg. “Would people have been inspired to do similar things? Would they have been completely out of fashion in 20 years? We felt it was important to take them beyond the drafting table. Animation seemed to be the most impactful and easiest way to do that.”

One of the most unique proposals was a massive civic center at Pittsburgh’s Point that would have seen the city’s three rivers converge around a 13-story circular building containing an opera house, three movie theaters and a convention hall, surrounded by a spiraling roadway.

“Today you see mega-structures like that all over the world — buildings with all of these different functions — but for Wright in the 1940s it was really a radical initiative,” Graff said.

The concept is part of a larger idea Wright explored, which Graff called a “broad-acre city.”

“The city itself is largely decentralized,” he said. “People live closer to nature, with certain urban functions concentrated in places like this civic center. And then you have the rest of the city more decentralized, to disperse other urban things more gently into the landscape.”

Using three-dimensional rendering technology to choreograph camera paths and to shape lighting to produce the same type of visual effects used in the film industry, Skyline Ink’s animations are presented throughout the exhibition to provide a multimedia experience. A viewing theater envelops visitors to show an expanded film of the three unrealized Pittsburgh designs.

The Pittsburgh-based Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild Jazz program also produced a musical score by Daniel May and Marty Ashby to accompany the exhibit.

Graff said the exhibit showcases Wright’s strong sense of unifying architecture with the surrounding landscape.

“As he was positioning buildings, whether it was something like Fallingwater or the apartment tower he designed that’s animated in the exhibition, he’s thinking about the vistas,” Graff said. “Even his interior floor plans create space that allows you to connect with the larger world outside the building.”

“Frank Lloyd Wright’s Southwestern Pennsylvania” will be on display at the National Building Museum through March 17. For more, see NBM.org.