Green Book helped African-Americans find welcoming places in Western Pa.

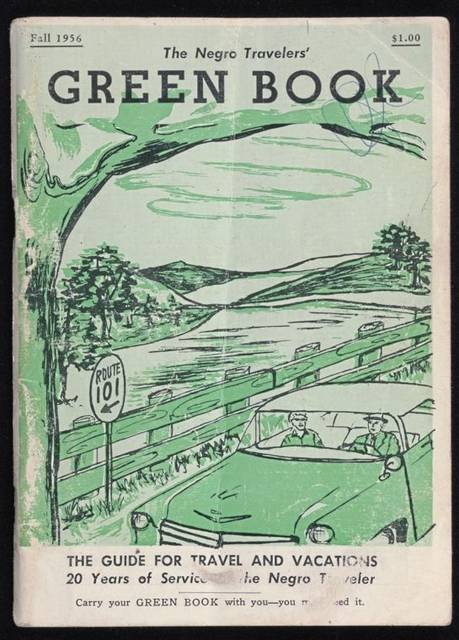

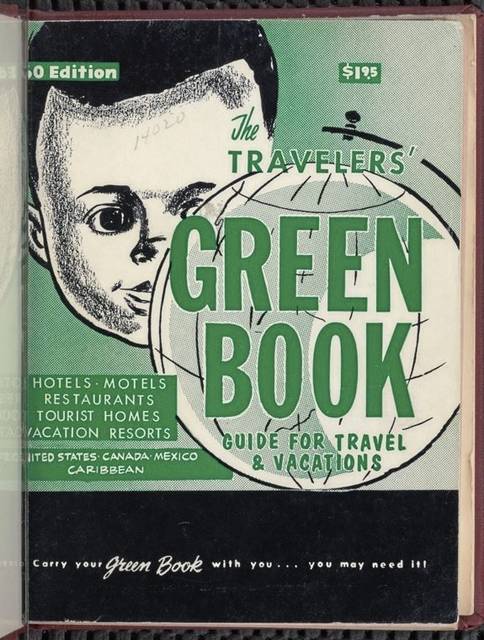

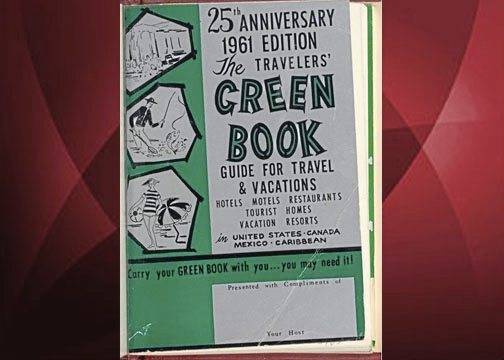

“Carry your Green Book with you … you may need it!”

That was not an empty advertising slogan in the decades from the 1930s to ’60s in the United States, where Jim Crow laws reigned in the South and de facto segregation was observed in the North.

In many cases, the savvy African-American traveler turned to the Green Book to find a place to stay or eat or get other essential services.

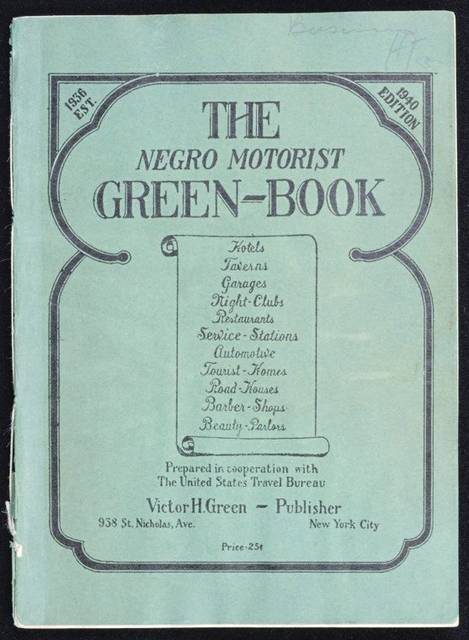

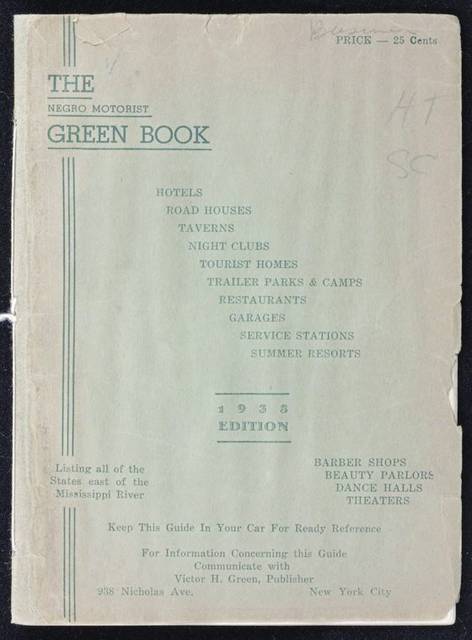

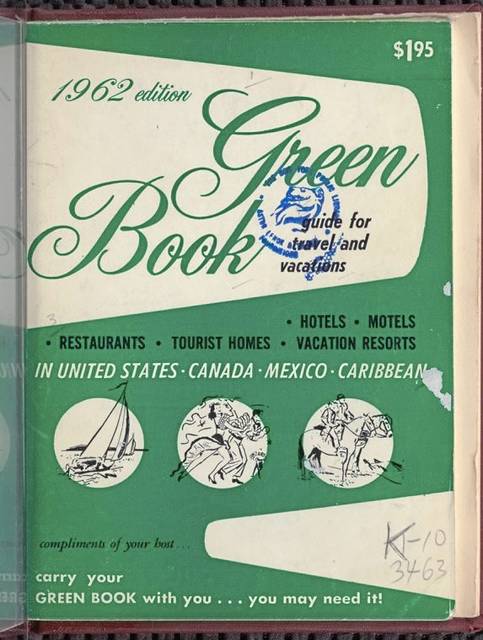

The traveler’s guide, now the subject of a major motion picture, started out in 1936 as a 16-page pamphlet and, by 1962, had become a 128-page book. Its listings included hotels, motels, gas stations, restaurants, “tourist homes,” barber shops, beauty salons and other businesses that were guaranteed to serve black motorists.

“It’s an important, almost forgotten, aspect of our history. I just want people to know that this was needed,” said Patrick Bochy, who has studied the Green Book’s place in Jim Crow America.

Bochy, executive administrator at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, will give a presentation on the Green Book at 1 p.m. Saturday at the Lincoln Highway Experience, 3435 U.S. Route 30, Unity. Registrations are due by Wednesday.

Bochy said he will focus on the 1940 edition of the Green Book, then known as the Negro Motorist Green Book. Its hundreds of listings covered 44 states, Washington, D.C. and, especially, New York City.

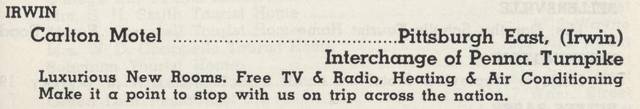

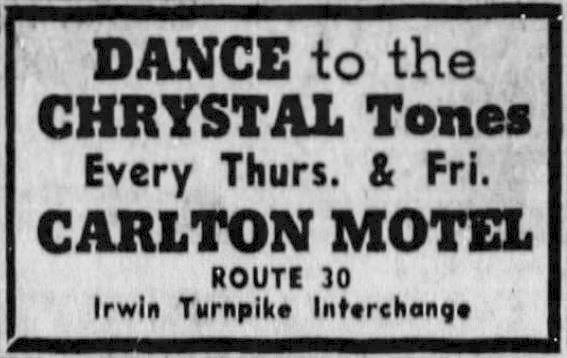

Listings for Western Pennsylvania were concentrated in Pittsburgh’s Hill District but also included establishments in Washington. Later, the Carlton Motel in North Huntingdon — though listed as Irwin — was added because of its proximity to the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

Bochy said he first learned about the Green Book in graduate school at Shippensburg University. Even though the 1950s were considered a golden age of travel, “that sense of freedom that comes with getting behind the wheel of your car wasn’t available to everyone,” he said.

African-Americans who traveled, whether in the North or the South, often had to make contingency plans.

“Many businesses would not serve African-Americans because of their skin color,” he said, “so many black travelers would do things like pack picnic lunches or make sure they had a full tank of gas. In some instances, they would take portable toilets because they didn’t know safe destinations to stop. They’d have to make arrangements to stay the night in a friend’s home or take detours far off their route. Sometimes they slept in their car.”

The Green Book, started by a resourceful black postal worker named Victor H. Green, provided listings and advertisements for businesses that served African-Americans without hassle, he said. Most of them were black-owned, but not all. The book’s publisher regularly solicited new entries from readers and correspondents.

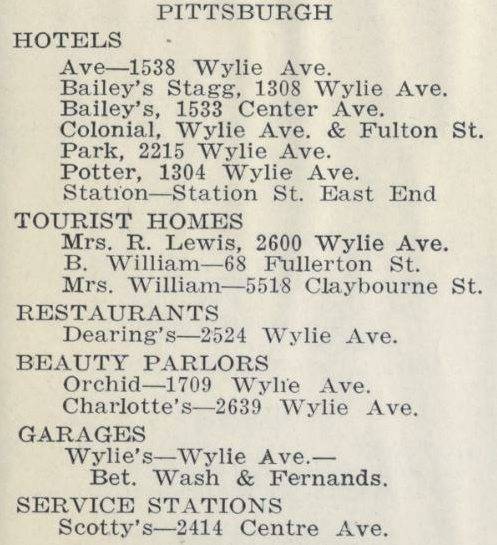

The 1940 edition contained 15 Pittsburgh listings including seven hotels, three tourist homes, one restaurant (Dearing’s Tea Room, 2524 Wylie Ave.), two beauty parlors, one garage and one service station.

Former Hill District resident Thelma Lovette, who died in 2014, recalled two hotels that were listed in the 1940 Green Book.

“Our people (independent of fame or riches) couldn’t stay at other downtown hotels. We opened our own. The Bailey Hotel was another of our hotels. Fondly I remember the Bailey for its doorman. That was impressive during those days. They had even a caterer, a restaurant, and room service. The Potter’s Hotel was another that offered Blacks welcome and comfortable lodging,” Lovette wrote for the 1999 document “Hillscapes: A Scrapbook.”

Dr. Liann Tsoukas, a University of Pittsburgh senior lecturer, said the Green Book helped African-Americans escape the bonds of public transportation, often a realm of segregation and humiliation, by enabling more free private transportation.

“Being able to get into your car was one thing, but being able to find a place to stay or get gas was another. Getting into your own car didn’t necessarily crack the system,” Tsoukas said.

Blacks had more independence and autonomy in the North, but that didn’t always translate into equal dignity or equal services, she said.

As a thriving African-American political, economic and cultural center, Pittsburgh had its share of opportunities for black travelers, she said.

“There were always safe places for blacks to go. African-Americans were pretty in tune with what the Hill District was, so I’m not surprised there aren’t more (Pittsburgh) advertisements in the Green Book,” Tsoukas said. “People knew the safe places of Pittsburgh.”

With the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Green Book eventually became obsolete, publishing its last volume in 1967.

The 1966-67 edition had a chapter, titled “Civil Rights: Facts vs. Fiction,” that explained how the law applied to public accommodations: “Effective at once, every hotel, restaurant, theater or other facility catering to the general public must do exactly that. Thirty-one state laws, already in effect, have even stronger provisions.”

Reservations for Bochy’s program are $12 each and include a tour of the Lincoln Highway Experience, a 60-page Lincoln Highway Driving Guide, a postcard with a stamp, and a piece of pie and cup of coffee in the restored 1938 diner.

To register, call 724-879-4241 or go online at LHHC.org, go to the Gift Shop tab and then click on Events.

Stephen Huba is a Tribune-Review staff writer. You can contact Stephen at 724-850-1280, shuba@tribweb.com or via Twitter @shuba_trib.

Remove the ads from your TribLIVE reading experience but still support the journalists who create the content with TribLIVE Ad-Free.