Like many American baby boomers, Randa Relich Milliron has vivid memories of the Apollo 11 moon landing on July 20, 1969.

The Belle Vernon native was in her early teens as she sat glued to a television set throughout the day and well into the night that culminated in the first men, Americans Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, walking on the moon.

“It was the all-consuming focus of my life at the time. Everything else besides that shining focal point was a blur,” Milliron said. “I was proud and excited. It felt like we all had done it. But it also made me want to do it personally. That was the day that ignited the spark that ended up with me having my own moon mission in the works.”

Fifty years later, Milliron points to that day as the catalyst for creating Interorbital Systems, the company she founded with her husband, Mt. Pleasant native Roderick Milliron, in the Mojave desert in California in 1996. Since then they have been working on a commercial rocket system with the long-range goal of a manned mission to the moon.

“The moon has always been our goal,” said Randa Milliron, the company’s CEO.

The Millirons are part of the future of American space exploration that is connected to Pittsburgh in a substantial way, just as it was during the 1960s.

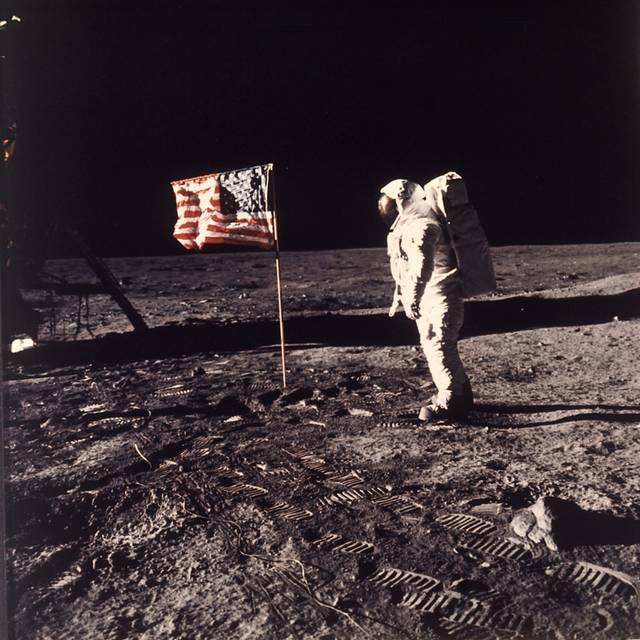

Western Pennsylvania innovators and companies played important roles in landing a man on the moon. Alcoa produced an aluminum hatch door on the lunar module Eagle that Armstrong exited before descending the ladder to reach the lunar surface, while Westinghouse created a camera that could operate on the surface of the moon. It captured Armstrong’s first step on the lunar surface, seen by millions of television viewers around the world.

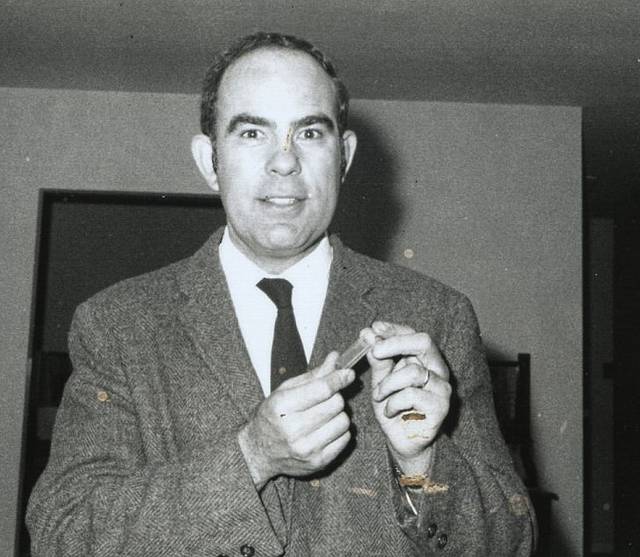

In 1969, Bruce Hapke, a University of Pittsburgh professor in the Department of Geology and Planetary Science, was as excited as anyone when Armstrong set foot on the moon’s surface.

Six years earlier, shortly after President John F. Kennedy announced the U.S. effort to reach the moon, Hapke published an academic paper that deduced what the moon’s surface would resemble. It was precisely what Armstrong found when he arrived. He said the surface appears “to be very fine-grained as you get close to it. It’s almost like a powder down there, it’s very fine.”

Before Hapke’s paper, NASA had no idea what the surface of the moon was like.

“The moon reflects light in a very peculiar way, unlike most materials, and I thought this might give a clue as to what the surface was like,” Hapke said.

He began to study what controls the way that light is reflected by a surface in different directions.

“After a good deal of work, I discovered that the only material that would do that was very fine-grained powder,” said Hapke. “So, I wrote this up and after it was published, NASA was extremely interested in it because, for the first time, they had something solid to go on in the design of things like astronaut boots and landing pads for space ships and rovers that would roll around on the surface.”

Hapke became part of an advisory panel for later Apollo missions to the moon. He was disappointed when the program ended abruptly after Apollo 17 in December 1972.

“I kept thinking, ‘Here we go, we’re on our way out into the solar system,’ and I was very excited and hoped to be part of that exploration. Unfortunately, it didn’t turn out that way,” said Hapke, now a Pitt professor emeritus who has a lunar mineral — hapkeite — named for him. “We went to the moon and never went back. It’s one of the big disappointments of my life.”

Reasons for stopping the program vary from dwindling interest on the part of the American public to the cost of the Vietnam War, which reduced federal funds for the space program.

But now the U.S. is going back to the moon — and a significant portion of that effort relies heavily on Pittsburgh-area people and institutions.

Think lunar, act locally

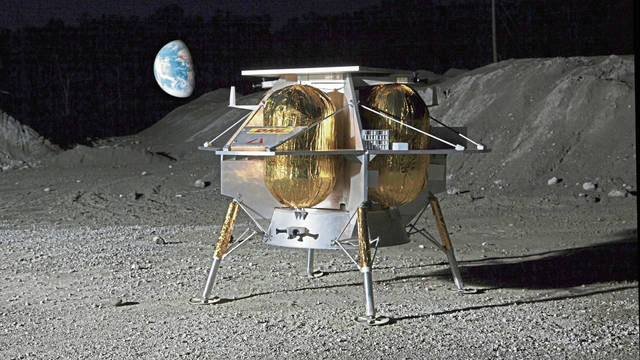

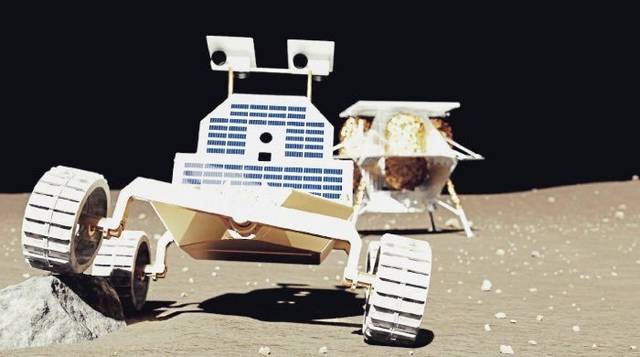

Earlier this month, NASA’s Lunar Surface and Instrumentation and Technology Payload program awarded a $5.6 million contract to the Pittsburgh-based company Astrobotic and its partner, Carnegie Mellon University, to develop an autonomous lunar rover.

The 13-kilogram rover known as MoonRanger is being developed to provide high-fidelity 3-D maps of the moon’s surface in areas such as polar regions and lunar pits. Carnegie Mellon also plans to send a smaller, toaster-oven-sized CubeRover, also known as the CMU rover, aboard a lander built by Astrobotic to the moon in 2021.

It will make CMU the first university in the world to put a robot on another planetary body.

“Who would have guessed that we would be the ones leading America back to the moon,” said Carnegie Mellon professor Red Whittaker, pioneer of the new technology essential for exploring lunar pits, characterizing ice, investigating magnetic swirls and deploying future mobile instruments on the lunar surface.

As part of the 50th anniversary celebration of Apollo 11, Astrobotic’s Peregrine lander is on display this weekend on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Astrobotic CEO John Thornton says Apollo 11 accomplished an amazing feat, especially considering the technology of 50 years ago.

“They had the incredible inventiveness and creativity to do as much as they possibly could do with what they had,” Thornton said. “To accomplish something like that is just remarkable.

“They had 450,000 people [employees and contractors] working for NASA developing many of the components that would fly the Apollo lander for the very first time. These components didn’t exist, like the flight computer and the sensors and the avionics and things that were needed to land. Nowadays there is a whole array of components you can just buy off the shelf.”

Thornton says Apollo 11 created the building blocks for the space industry that exists today. For Astrobotic, the goal is to land commercial payloads on the moon.

There is also a new Trump administration plan for returning humans to the moon. Instead of the original NASA target date of 2028, the schedule now calls for a manned mission within five years.

Whittaker, who described the Apollo 11 mission as the “pinnacle of human and technological achievement,” said the future of moon exploration will be as much about robots as humans. Robots, with “their innate advantages,” will end up doing a lot of the work, he said.

“With humans, you’ve got to feed them, you’ve got to keep them breathing. You need time out for sleep. With robots you don’t have the self-maintenance,” Whittaker said.

Whittaker noted the enormous risks taken with the Apollo astronauts, including the potential of exposing them to high levels of radiation from sun flares that can occur spontaneously.

”There is nothing in the little lander or little spacecraft that’s going to protect you from that kind of high-energy radiation. But they lucked out because they didn’t have the sun flares,” Whittaker said. “You see that again and again and again at that intersection of human and technical pursuit.”

Whittaker said the results of the Apollo 11 moon landing sharpened his focus on what he wanted to do with his life.

“It just transformed my view of space exploration and the technologies that go into it. I knew then that I would be a part of it in some way.”

On to Mars, and beyond

Hapke said the moon could play an important role in getting people to Mars.

“I hope we’ll see a man on Mars before I die. NASA’s original plan had men on Mars in 1993,” Hapke said.

Hapke said a good way to reach Mars would be to build a space station on the moon and launch from there. He envisions astronauts and equipment being ferried up from Earth and rockets being refueled on the moon. One thing you wouldn’t have to haul up would be hydrogen and oxygen, which are the primary fuel in rockets.

“You can make hydrogen and oxygen from water. There is evidence of water in permanently shadowed craters, so that would be a natural resource we could utilize if we built a base on the moon,” Hapke said.

“That would save a lot in the size of the rocket you would need to launch. If you launched a rocket from the Earth to Mars, it would have to be a lot bigger than if you launched one from the moon,” he added. “That’s a primary reason for building a base on the moon.”

Meanwhile, in the California desert, the Millirons are making plans to take that vision a little further with a lunar colonization program involving their own NEPTUNE rockets carrying adventurous people back and forth from the moon. They said it would begin with a manned flight within 10 years.

“We want to set up a commercial colony on the surface of the moon, whereas NASA would be more like an Antarctic research station with no frills. We want to have living areas and night clubs and casinos,” Roderick Milliron said.

“We want to have all the cool things that you would want at a resort destination,” Randa Milliron added. “It will have the feel of a military base and a luxury resort, a high-adventure resort.”

The Millirons said their flights will range from $2 million to $5 million per person — relatively affordable for the average high-net-worth individual.

“The NASA cost is always going to be astronomically high. Very few people or entities can afford to use NASA’s space launch system at the price they charge. You practically have to be a nation to use it,” Randa Milliron said.

“We would like to be the Southwest Airlines of spaceflight because this is a bargain, no-frills class of space travel. We had to pick up the mantle essentially. We had to do this thing and that’s what we’ve been doing for the last two decades, working towards that goal,” she said.

And to think that it all started with “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”