Don Aliquo doesn’t skip a beat when asked to share his formula for a music career that began with sing-alongs around the piano as a toddler and shows little sign of slowing down at age 93.

“What’s my secret? Those 11 steps outside this door and this,” he says with a tap to the neck of the vintage Selmer saxophone at his side.

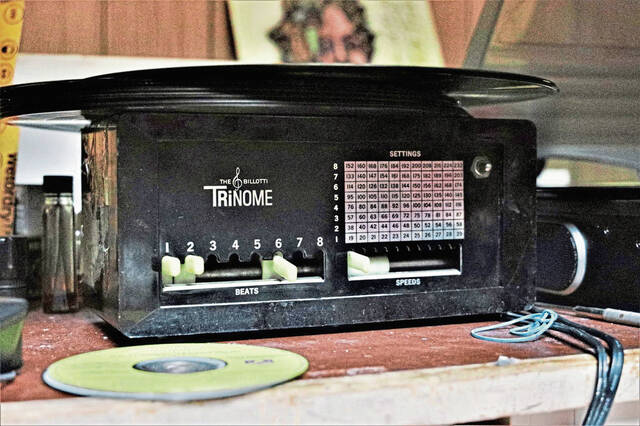

The retired Highlands High School music teacher said going up and down the stairs to his basement music studio keeps him limber, while hours of rehearsing complex jazz scores keep his lungs pumping, fingers nimble and mind sharp.

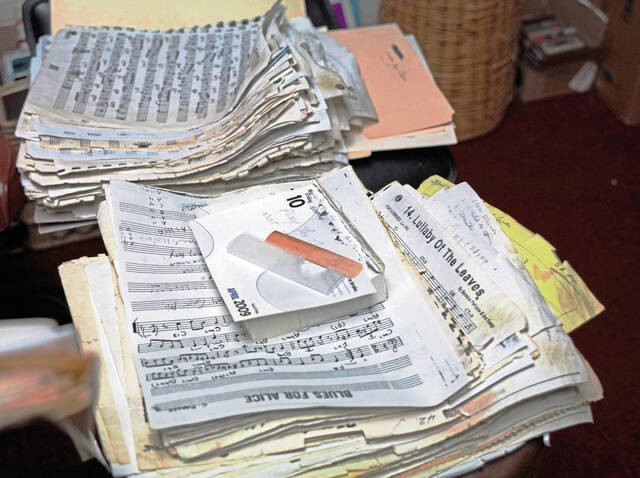

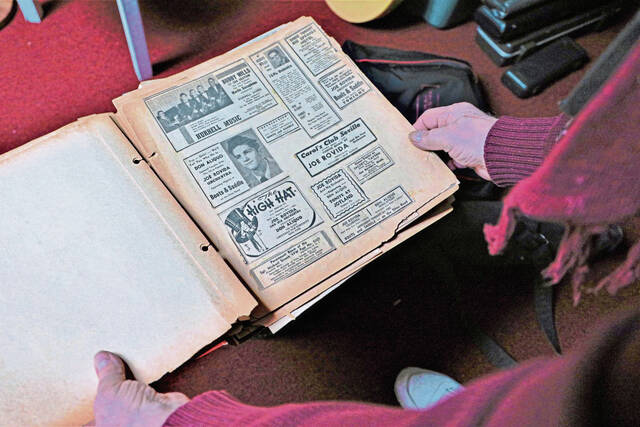

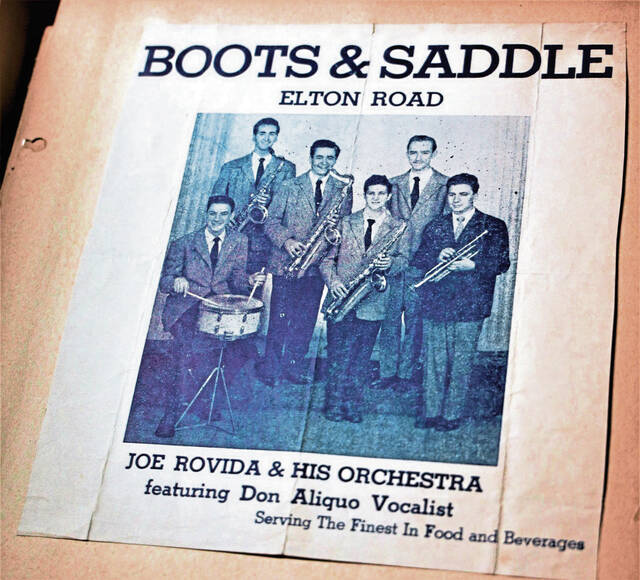

While the music studio in his Lower Burrell home is filled with snapshots, newspaper clippings and posters chronicling the many people and places he encountered as a performer, the tiny room is not about preserving the past.

The hours Aliquo spends rehearsing keep him tuned for a regular schedule of performances, which include weekly gigs at the 3rd Street Gallery in Carnegie along with shows throughout the region.

“When I started teaching at Highlands in 1956, I didn’t put my horn in the case and forget about it,” Aliquo said. “I played out every chance I could. I felt it made me a better teacher because I was able to share that experience with the kids.

“If you’re going to ask kids to perform, then you better perform for them. I think it’s one of the greatest tools you can have as a music teacher,” he said.

The son of Sicilian immigrants, Aliquo grew up in Johnstown during the Big Band era and was heavily influenced by listening outside a venue when orchestras led by Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw performed in the city.

“My sister played the piano, and my family and the neighbors would sing along for hours,” Aliquo said. “I started performing as a vocalist when I was 13 years old and started getting some recognition. Then I started taking clarinet and then saxophone, which I really fell in love with.”

In the years after graduating high school, Aliquo took to practicing music six hours a day in preparation for an audition for the Walter Reed Army Band, which he passed.

“Until I made the decision to pursue music as a career, my dedication to rehearsing was kind of sporadic,” he said. “But once I decided on music, I went all in and started putting the time and work in that I needed.”

Aliquo said living in the Washington, D.C., area while in the Army provided him with a wide range of musical experiences.

“It was the best thing I ever did in my life,” he said. “It gave me the chance to take lessons from some of the finest musicians in the military and to perform constantly at all different levels.”

He said two performances during one weekend in that period embodied how varied the experience could be.

“I went from playing for President Truman’s second inauguration on one night to playing a private show with a group for a dance at a tiny place in a poverty-stricken section of Chevy Chase (Md.).”

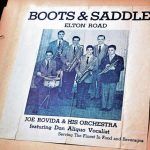

After leaving the military, Aliquo continued performing with several groups and as an “itinerant” musician, picking up gigs with touring national artists who frequently hired local musicians for their shows.

He used the GI Bill to study music at what is now Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Aliquo said he decided to enter teaching after a summer touring East Coast beach towns with an orchestra.

“We wound up doing shows that I really didn’t care for,” he said. “We were hired as a jazz group, but that’s the time Bill Halley and rock ‘n’ roll hit like a ton of bricks, so we had to do that. It was a great experience, but it wasn’t the music I wanted to play.”

While Aliquo admits that he didn’t have a calling to teach like so many in the profession, he quickly learned that what he had could be used as a valuable teaching tool.

“I was able to relate many of the experiences I had performing to my teaching in a way that gave kids a quality music education,” he said.

And rather than ignore the contemporary music his students often preferred, Aliquo found ways to expand what they were listening to by helping them explore the connections to different styles and forms.

“I had a couple of kids in class who were really interested in the avant-garde band King Crimson,” he said. “So I gathered up a bunch of John Coltrane records to play for them so they could compare what they were hearing to what they’d been listening to.”

Aliquo retired from Highlands in 1992 after 37 years teaching in the district.

He said his biggest accomplishment as a teacher was passing along his musical knowledge to his son, Don Aliquo Jr., who teaches music at Middle Tennessee State University and is a respected jazz artist in the Nashville music scene.

“I used to teach him, but now he can teach me,” Aliquo said about his son. “I’m proud of him but also a little jealous of how good he is.”

Aliquo, who moves a little slower than he used to but suffers from no significant physical ailments, said he cannot imagine hanging up his horn.

“Playing music and performing have always been such a big part of my life,” he said. “And I’m going to do it as long as I’m able and there are people who want to listen.”

For more information about Aliquo’s upcoming performances, visit his Facebook page at facebook.com/don.aliquo.1.