Successful growth of baby mussels in Kiski River indicates continued health of waterways

Several years ago, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy biologists documented the first freshwater mussels — eight species in all — found in the Kiski River in over a century. Then, last summer, the biologists implanted some baby mussels in concrete silos in the Kiski, as well as a dozen other waterways, to see if conditions had improved enough for them to survive.

Native fresh-water mussels are indicators of good water quality. They cannot tolerate a highly polluted and compromised aquatic habitat.

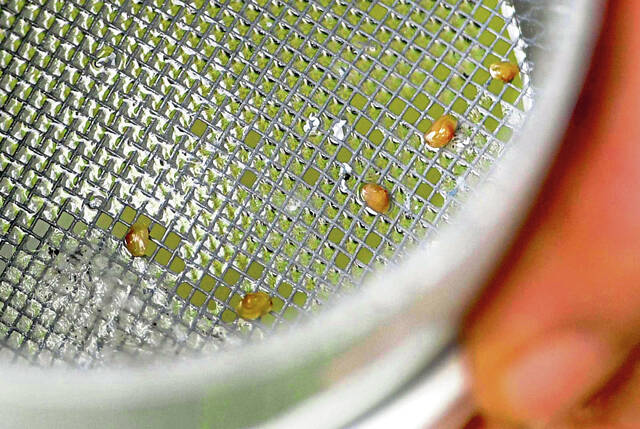

The Kiski River youngsters not only survived but doubled their diminutive size of 3.5 millimeters — the length of a half-grain of rice — after only about three months, said Eric Chapman, the conservancy’s director of aquatic science. Adults of various species range from about one to eight inches long in local waters, he said.

“Juvenile mussels are more sensitive than older ones — if there isn’t enough food in the water, they won’t survive,” he said.

“The Kiski is, indeed, on the road to recovery and the proof is in the silos we had out last summer,” Chapman said. “We had 87% survival of the juvenile mussels, which is outstanding.”

The conservancy will present “Meaningful Mussels,” a free public webinar on their mussel project and how these mollusks live, at noon Friday, April 22,.

They partnered with the U.S. Forest Service’s Wendell Haag and the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission on the state’s first effort to implant concrete silos with juvenile pocketbook mussels in 13 Western Pennsylvania streams.

The scientists wanted to test the waters, literally, for what they call “mussel recovery readiness” to see if water conditions were right for the mollusks to survive and grow.

For the study, half of the waterways chosen by the conservancy once hosted mussels and lost many or all of them to pollution in the past century.

Pollution from tanneries, alcohol production and other industries along waterways degraded water quality, as did pollution from coal mines, Chapman said.

Results are promising for the Kiski River and other formerly impaired waterways to serve as homes for a whole new generation of mussels.

The presence of the mollusks not only boosts water quality but adds to biodiversity. Large mussel beds also can stabilize stream bottoms.

“Mussels provide clean water at no cost,” Chapman said.

Depending on the size of the mussel, which also is known as a filter feeder, a single one can filter two to 20 gallons a day, he said.

Large numbers of mussels, known as mussel beds, can clean a significant amount of water: From 2015 to 2018, the conservancy and the Fish and Boat Commission transplanted 36,000 mussels from a bridge project on the Allegheny River to the Clarion River.

Those mussels filter about 100 million gallons a day, according to estimates from Chapman. The conservancy is working with the fish and boat commission mussel hatchery in Union City in the northwestern part of the state to grow the number of young mussels to reintroduce to waterways recovering from pollution, said conservationist Mary Walsh.

“There’s interest in more study,” she said. “All the information is paving the way to eventually restoring the Kiski with mussels.”

Mussels also become part of the food chain, eaten by freshwater drum, muskrats, raccoons and other animals.

In addition to the Kiski, the conservancy and the forest service placed mussel silos last year in the Allegheny River, Beaver River, Dunkard Creek, Ten Mile Creek, Mahoning River, Shenango River, Sandy Creek, French Creek, Tionesta Creek, Clarion River, Little Mahoning Creek and Mahoning Creek.

Remove the ads from your TribLIVE reading experience but still support the journalists who create the content with TribLIVE Ad-Free.