Westmoreland County missed the highs and lows of the civil rights movement that rocked the nation throughout the 1950s and 60s.

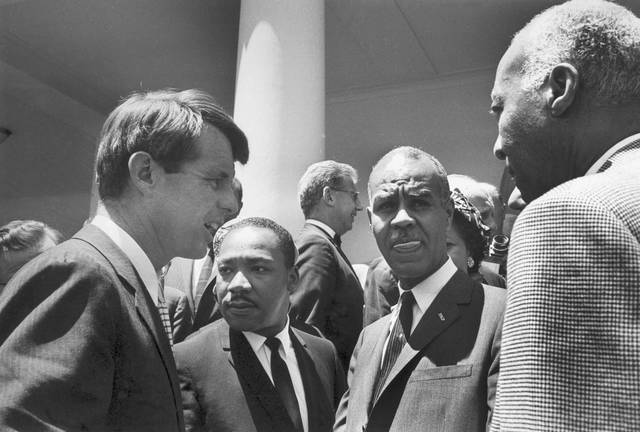

But there were a number of issues brewing just below the surface, a panel of “seasoned” county natives told an audience Monday at Westmoreland County Community College during “a look back” at their experiences during and after the civil rights movement.

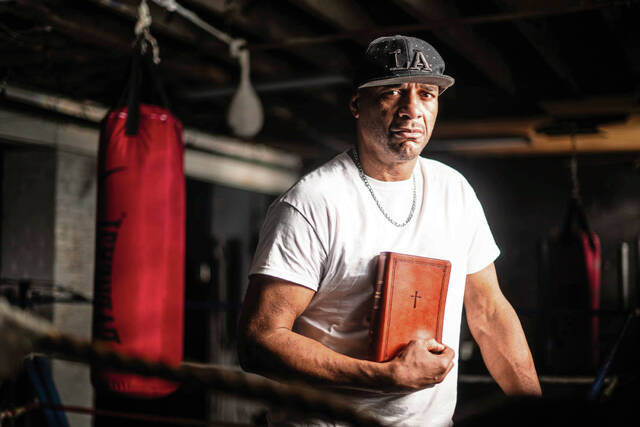

Carl Brantley Jr., 71, of Greensburg, said he never experienced discrimination as a Hempfield Area High School student. But when he became West Penn Power’s first black employee in 1969, things were rough, he said.

Homeowners in Youngwood and Latrobe called the police on him, in disbelief the young man in a utility company uniform driving an iconic orange power company truck belonged in their community, he said.

The tall, stately retiree who spent 38 years on the job before retiring in 2007 prefers to focus on a white co-worker. “He treated me like I was his son. I ate at his house all of the time,” Brantley said.

Keith Houser, 64, of Greensburg, a retired lawyer, said he slammed into an invisible color barrier as a young lawyer after one of his first bosses took him to a local bar and bought him a drink. Houser, who grew up in New Kensington “where it felt like half of the people were black and half were white,” said he left feeling good until his boss told him the bar owner undoubtedly smashed his glass and laughed about it as soon as they left.

The crowd listened as Houser shared the conversation he had with his son when the boy turned 13. He said he instructed his son, as his father had instructed him and his grandfather before him had instructed his father, to always be respectful of police and answer everything “yes, sir” and “no, sir,” so he did not wind up in the morgue.

Tay Waltenbaugh, Westmoreland County Community Action executive director, recalled growing up in West Tarentum, where lower income white families like his lived on one side of the tracks and black families lived on the other side. They came together to play baseball and basketball, but none of his black teammates ever came to the YMCA that Waltenbaugh haunted day and night.

“Everything was segregated, but no one talked about it. I see things in a different perspective now,” said Waltenbaugh, 64, of Hempfield.

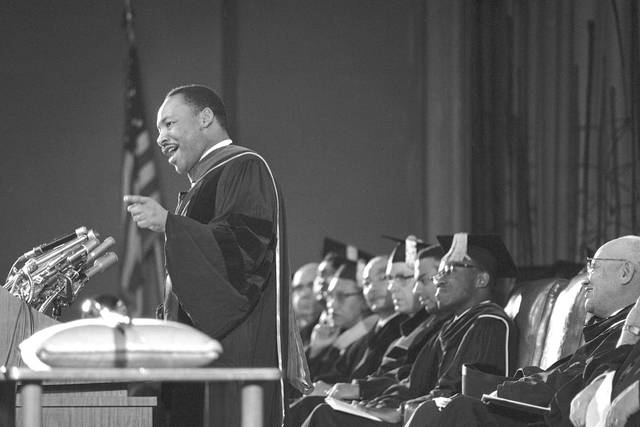

Panel moderator Carlotta Paige, 71, co-founder of the Westmoreland County Diversity Coalition, said stories like that point to issues that remained under the surface here as civil rights became the law of the land, national guard troops helped integrate schools in the South and cities across the nation rioted in the wake of the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Things were relatively quiet in a county where minorities made up only 5 percent of the population.

“One of the reasons people think things are OK here is because the blacks here didn’t raise a ruckus,” Paige said. “The things that happened to us, people didn’t pay much attention to.”

She said she was recruited to integrate Westinghouse’s Youngwood facility when she finished high school.

She recalled how a good friend she made at the plant, a young white woman about her age, invited her to her parents’ home for dinner.

“She didn’t tell them I was black. They threw a fit and threw me out,” Paige said.

Lori Sabo, 74, a retired legal assistant, said discrimination was alive and well in Hempfield when her daughter, a white woman who is married to a black man, went to see a house where the couple hoped to settle.

“When my daughter got there, everything was great. My daughter did all the talking and the (owner) hugged her. Everything was great until my son-in-law pulled in and all of a sudden it was ‘this house is taken,’” Sabo recalled.

Paige, who lived and worked in New York City for 23 years before returning to the Greensburg area, said she loves Westmoreland County. But she said the community must work to be more inclusive of minorities of all types.

“We took a look back and our experience was good, our experience was bad. But looking forward, we have to make it better,” Paige said. “We have to become a more welcoming community. The economic welfare of our community is going to be undermined if we don’t become a more welcoming community. We’re an aging community and people who are going to come here, won’t come unless they feel welcome.”