Schools, lawmakers seek answers to bullying

Share this post:

State Rep. Brandon Markosek is familiar with the effects bullying can have on a young child: He did not speak until he was 3 years old and developed a stutter just as he was about to hit his teenage years.

“By the time I hit 14, certain words or syllables, I just couldn’t say,” said Markosek, D-Monroeville. “I still battle that to this day, although it’s not nearly as bad as it used to be. But I was bullied for not sounding right.”

When Markosek, 27, was in middle school, there was precious little in place for school districts to address bullying. And while there are anti-bullying initiatives like the Olweus program taking root in districts across the country, it remains a complex issue to tackle for school officials as well as parents.

In the classroom

Most bullying takes place on school grounds or on the school bus, according to StopBullying.gov, an arm of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Recognizing that, school districts including Franklin Regional, Burrell and Hempfield Area have adopted the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program.

At Franklin Regional, “there was nothing systematic in place, no common language around the topic of bullying,” said high school principal and national Olweus trainer Ron Suvak. “It was really about, how do we address the norms in our schools, and what are the expectations we have for our students at all levels?”

Suvak said the Olweus program provides a good framework to address bullying, “but if we just put it into place and didn’t address behavioral and cultural expectations and how we’re going to treat student behavior, the program’s not going to work.”

Promoting an environment with clear behavioral expectations, having teachers and staff model the behavior they want to see in students, and responding appropriately when an issue arises is the way to make the program work, according to Suvak.

“It’s people, not programs,” he said.

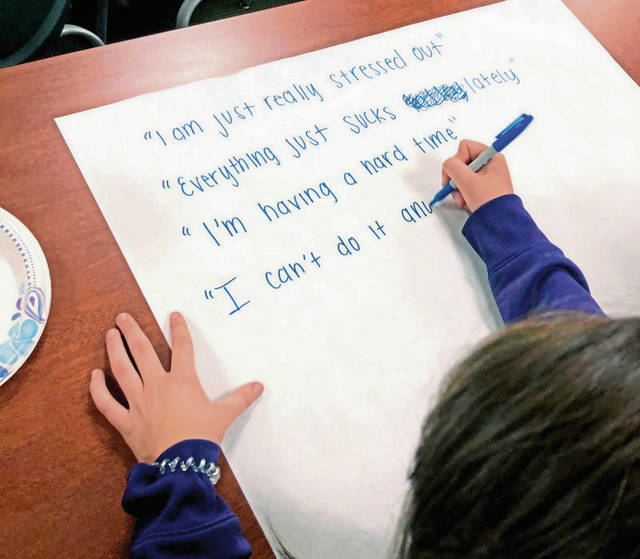

At Penn-Trafford High School, senior Zach Rocco heads the Active Minds club, a local chapter of a national nonprofit with the goal of opening up conversations about mental health and student stress.

“Sometimes kids don’t want to talk to a guidance counselor, and we’re sort of that bridge,” Rocco said.

Active Minds’ philosophy is represented by V-A-R: Validate a person’s feelings if they bring a problem to you, appreciate the courage it takes to start that conversation, and refer that student to a resource that may help.

“It’s helping to create a positive culture,” said Zach’s father, Jim. “It’s trying to teach the student body how to be more comfortable with reaching out. The kids hand out wristbands that simply say, ‘You good?’ The idea is to spark a conversation if one needs to happen.”

Say something

Conversation is crucial for Suvak.

“The No. 1 thing is to tell kids: We want them to tell us if something is going on,” Suvak said.

That is frequently easier said than done. University of Virginia professor Dewey Cornell and University of Missouri associate professor Francis Huang’s 2015 research into the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs showed limitations inherent in nearly every type.

The Olweus program, for example, relies largely on anonymous self-reporting.

“School authorities may learn how many students are being bullied, but they do not know who is being bullied and therefore cannot directly intervene to stop the bullying until they observe the bullying or someone comes forward to report it,” Cornell and Huang wrote.

Some programs promote peer nominations, where students can anonymously report a situation they believe to be bullying, so it can be more directly addressed.

“Students might not be comfortable with nominating their peers because it might seem like ‘snitching,’ ” Cornell and Huang wrote.

Suvak acknowledged that getting students — particularly those in high school — to open up is a challenge.

“For so long, parents, schools, social media, everyone says, ‘Mind your business,’ ” he said. “But if there’s one thing we try to get across, it’s that if you see something or know there’s a situation going on, tell a teacher at school or an adult at home.”

Defining ‘bullying’

For Markosek, any efforts by the state to curb bullying are being hampered by the lack of a clear definition. He and fellow co-sponsors of House Bill 2053 and its Senate companion, Senate Bill 564, hope to provide that definition.

“Right now, under the Pennsylvania Crimes Code, ‘bullying’ is not defined at all,” Markosek said. “It gives district attorneys another tool, per se. Right now, they’re kind of restricted in what they can charge.”

If an instance of bullying is determined to have risen to the level of disorderly conduct, simple assault or harassment, it is charged appropriately.

Markosek’s legislation defines bullying specifically as committing a defined crime with the intent to “1) harass, annoy, alarm or intimidate another individual or group of individuals, or 2) place another individual or group of individuals in fear of bodily injury or property damage.”

It would classify such behavior as a third-degree misdemeanor, with more severe penalties for more severe instances.

The legislation is assigned to the House’s Judiciary Committee.

Communication is key

The goal of all anti-bullying programs is to identify a problem and intervene before it gets out of hand, Suvak said.

“What we can reinforce to our students and their parents is, if this is continuing, we want to know,” he said.

While “cyber-bullying” is the least prevalent form of bullying, according to StopBullying.gov, it’s nonetheless a worthwhile concern for administrators such as Suvak.

“Unlike when I was growing up, with the rise of social media, interactive gaming systems and real-time chat, that can open things up to a 24-hour cycle,” he said. “No student deserves that.”