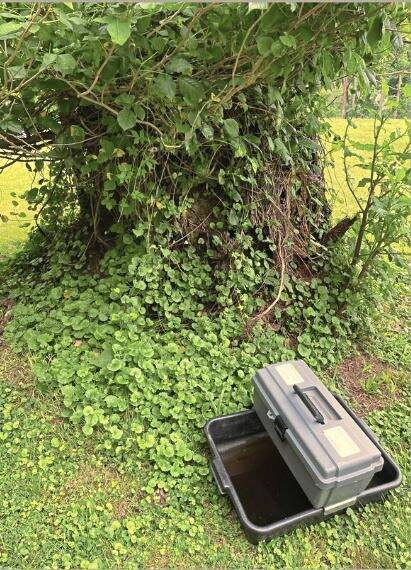

Beginning Monday, Chrissy Edwards-McCune will be out and about in Westmoreland County — setting traps to collect mosquitoes that might be infected with diseases and could bite humans and make them sick.

“I’ll set traps at about 30 sites each week,” said Edwards-McCune, who is a West Nile virus technician with the Westmoreland Conservation District office. “I’ll do it through Oct. 11.”

In partnership with the state Department of Environmental Protection, the captured bugs are tested to see if they are carrying certain diseases, including West Nile virus.

The results help state officials to track the spread of the diseases and to identify specific areas that warrant spraying to control the mosquito population.

Weather can affect the timing of the mosquito season, according to Edwards-McCune.

“Rainy weather that results in persistent standing water provides habitat for mosquitoes to reproduce,” she said. “Mosquito larvae was found as early as the second week of March in Westmoreland County.”

She normally begins checking for the larvae in mid-April, by dipping a cup on a long pole into standing water.

During the 2023 monitoring program, 12 adult mosquito samples collected in Westmoreland County tested positive for the West Nile virus.

Among neighboring counties, there were 142 positive West Nile virus samples in Allegheny, 12 in Fayette, and 13 in Cambria. There were more than 2,500 positive test results throughout the state; York County’s 286 led the way.

There were 22 reported cases in Pennsylvania of humans being infected by the virus last year, including one each in Allegheny, Fayette and York counties.

Armstrong County was the source of four of the 38 mosquito samples in the state that tested positive in 2023 for Jamestown Canyon virus, a recent arrival in the region. Luzerne County, with 18, led Pennsylvania.

According to the Pennsylvania Department of Health, the virus first was identified in 1961 in Jamestown Canyon, Colo.

“It’s been in our neighboring states for a while now,” said Edwards-McCune. “We started looking for it, and last year they actually started finding it in Pennsylvania. It didn’t show up in our county.”

Different viruses, vectors

She noted the Jamestown virus primarily is transmitted by the Aedes family of mosquitoes. Adult Aedes typically have a narrow black body with patterns of light and dark scales on the abdomen and alternating light and dark stripes on the legs, according to Britannica.com.

“They like floodwater areas,” Edwards-McCune said.

By contrast, she said, mosquitoes belonging to the Culex family are associated with the spread of West Nile virus, which has been in Pennsylvania since 2000.

The virus was discovered in 1927 in the West Nile sub-region of Uganda. It made its way to the United States in 1999, when the first case was recorded in New York City.

In the Eastern United States, the virus is primarily spread by the Culex pipiens, known as the Northern House Mosquito. Light brown, the adult female has pale abdominal bands, according to the Rutgers Center for Vector Biology.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 80% of people who are infected with West Nile virus don’t develop symptoms. Those who do may experience fever, headache, body aches, joint pains, vomiting, diarrhea or a rash. Most sufferers recover completely, but fatigue and weakness can last for weeks or months.

About 1 in 150 may develop a serious illness, such as inflammation of the brain or of membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord. Of those severe cases, about 10% result in death, the CDC says.

Likewise, a Jamestown Canyon virus infection can result in many of the same symptoms, with the possible addition of a cough, sore throat or runny nose — though many don’t experience any symptoms, according to the state Department of Health. Severe cases, with brain or spinal inflammation, also are possible, but deaths have been rare.

Picking up ticks

Mosquitoes aren’t the only troublesome bugs Edwards-McCune hunts on behalf of state officials.

Since mid-April, she’s been collecting ticks that are tested for transmissible illnesses including Lyme disease. It’s a biweekly task she will continue until the end of August, visiting about four sites each time she heads into the field.

People and animals can pick up dark-colored ticks by brushing against grass or leaf litter where the tiny bugs may be hiding. Edwards-McCune collects them by dragging a white cloth along the edge of local parks.

“For ticks, the program is a little different,” she said “There’s not any control measure we can take for them. We’re trying to collect data and see what diseases are out there.”

Spread to humans by the bite of an infected tick, Lyme disease can lead to fever, headache, fatigue and a skin rash. According to the CDC, if it’s left untreated, the infection can spread to joints, the heart and the nervous system.

Another tick-borne disease is babesiosis, the CDC notes. The parasitical disease leaves many symptom-free while others may have flu-like ailments. If it infects the red blood cells, it can cause anemia.

It can be life-threatening for the elderly and those with a weakened immune system or a serious underlying medical condition.