Three high-profile wins by progressive candidates in last week’s Democratic primary punctuated a shift in the party in Allegheny County that has been years in the making, political observers say.

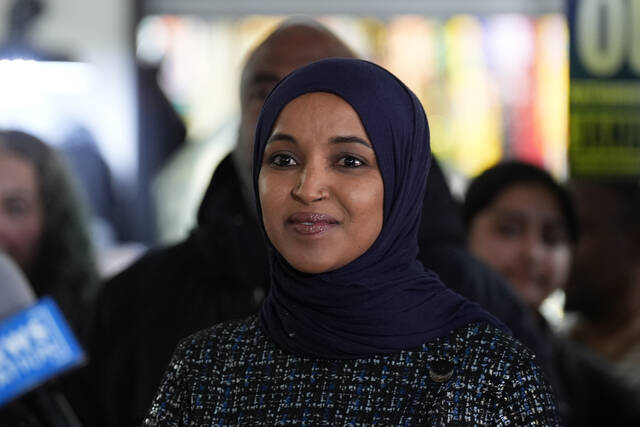

In recent years, progressive candidates have increased the county’s delegation of women in elected office and broken barriers by bringing Pittsburgh its first Black mayor, Ed Gainey, and Pennsylvania its first Black woman in Congress, U.S. Rep. Summer Lee of Swissvale.

Then, on Tuesday, three progressive candidates defeated more moderate opponents in hotly contested Democratic primary races. State Rep. Sara Innamorato won a six-way race for Allegheny County executive, Chief Public Defender Matt Dugan defeated longtime incumbent Stephen A. Zappala Jr. in the race for district attorney and Allegheny County Councilwoman Bethany Hallam easily won the party’s nomination in her race for another term in an at-large council seat.

No longer outsiders, two of the three progressive candidates — Dugan and Hallam — went into their races with endorsements from the Allegheny County Democratic Committee. Hallam also was the incumbent in her race.

Lee said the victories were the culmination of years of successfully organizing politically progressive groups into a coalition. The organizations include service workers unions, liberal nonprofits, environmental advocates, Black-led groups, progressive Jewish groups and criminal justice groups.

“Five years ago, we were nobody. But now there is a movement,” Lee said. “Western Pennsylvania is supposed to be the home of Blue Dogs (conservative Democrats) and the old boys network, but we have infiltrated and expanded that electorate.”

What is a progressive?

The term “progressive” has been applied to a broad array of politicians, and, given its recent successes, many local candidates have tried to take up the progressive mantle in their campaigns.

When asked for her to explain what being a progressive means, Lee said her definition is simple.

“Progressive means folks who are seeking to advance us,” she said. “Advance racial justice, environmental justice and social justice. Not just in our world, but in our politics.”

She said progressive candidates are listening and responding to Democratic voters’ desires to see more equity in areas such as the economy and the criminal justice system.

Ben Forstate, an election analyst who ran Allegheny County Controller Corey O’Connor’s successful primary campaign, said the county’s progressive voting bloc is growing.

The bloc includes what Forstate calls “institutionally minded progressives” and “outsider progressives” who are more skeptical of working within the county’s existing institutions.

The institutionally minded progressives represent a plurality of local Democratic voters, but not quite a majority, and are less skeptical of existing institutions, Forstate said. He said these progressives want leadership to be more reflective of the county’s increasing diversity and more assertive about implementing progressive policies.

Being able to combine these two factions has been a politically effective strategy against the section of the party that is made up of older, more conservative Democrats, Forstate said.

“No group of voters has a lock on the electorate, so you have to join hands,” he said. “So when outsider progressives can appeal to the institutionalist or the institutionalist can appeal to outsider progressives, it appears to be a winning formula in Allegheny County Democratic primaries.”

Lee said politicians who want to appeal to progressives can’t just operate from within institutions. By ignoring outside perspectives, lawmakers can become detached from many voters in the electorate, she said.

Changing movement

For decades, Democrats in Allegheny County operated through machine-style politics, tapping into a network where political favors such as jobs and services were implicitly traded for votes, Forstate said.

That has started to change, he said.

This became evident over the past few years when several candidates who were endorsed by the Allegheny County Democratic Committee went on to lose their races to progressive challengers. For a time, after the committee controversially endorsed a candidate who openly supported former President Donald Trump, some progressive candidates refused to seek the committee’s endorsement.

Allegheny County Treasurer John Weinstein picked up the committee’s endorsement this year in the six-way race for county executive but wound up losing by 8 percentage points to the progressive Innamorato. Forstate said Weinstein’s campaign appealed to many traditional, more conservative Democrats, but that wasn’t enough to win the party’s nomination — especially in such a crowded race.

“I think what is replacing the machine, in some ways, is a coalition of groups,” he said.

Lee pointed to 2018 as the year when a coalition of like-minded progressive groups came together and pushed for candidates outside of the traditional, machine structure.

That year, Lee and Innamorato ran successful primary challenges for state House seats occupied by members of a powerful political family, the Costas, without the endorsement of the local Democratic committee.

They were backed by many of the same progressive groups that were part of this year’s successful campaigns. Lee said these groups include the Alliance for Police Accountability, One Pennsylvania and environmental groups such as PennEnvironment and Food and Water Action, along with Lee’s own political action committee, Unite PAC.

Lee said these groups coming together resulted from demand in the electorate to see better representation out of elected officials, in both diversity of identity and policy.

“It took a lot of work and organizing to bring this coalition together,” Lee said.

Forstate said that work has been even more successful because many people associated with or supportive of those progressive groups also have joined the Allegheny County Democratic Committee.

This year saw a number of progressive candidates, including Dugan and Hallam, easily secure endorsements. It’s another sign that Allegheny County has moved away from Democratic politics as usual, he said.

Shifting electorate

While progressive candidates have been effective at organizing progressive groups into a powerful coalition, Forstate said the candidates also have been boosted by changing demographics.

As far back as 2007, Forstate said Patrick Dowd, 39, ran a successful campaign against a 50-year-old incumbent in Pittsburgh City Council’s District 7 when the area started seeing an influx of younger residents.

Forstate said Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald’s 2011 campaign was critical of the old-school style of Democratic politics and he ran to the left of his opponent on several issues. In recent years, however, Fitzgerald has supported opponents of progressives such as Lee, Innamorato and Hallam.

And since the late 2000s, Allegheny County’s Democratic electorate has grown younger and more diverse, boosting the chances of local progressive candidates, Forstate said.

“If the rest of the country wants to see what role millennials play in government, they should look at Allegheny County,” Forstate said.

This shift has been centered in the city of Pittsburgh but also is happening in some suburban areas. Forstate said Innamorato won many precincts along the Interstate 279 corridor in the North Hills and the Route 19 corridor in the South Hills, which he said have seen an influx of millennials and young families.

“This is a national trend. It is just magnified here by the demographics,” Forstate said, noting that the steel industry collapse of the 1980s led many Gen Xers to leave Pittsburgh and the rise of the area’s universities and hospitals has attracted Democratic millennials who are more likely to support progressive candidates.

Fitzgerald acknowledged the progressives’ successes.

“There is no question that the progressive wing of the party has a lot of energy,” he said, agreeing that changing demographics have contributed as the county’s young voting-age population has increased.

“Whatever your electorate is, you have to be serving that electorate,” he said. “Are we going to be like Seattle and Portland? We will see. One thing is for sure, it is a different Pittsburgh than a lot of us grew up in.”