Arraignment is the first step in the journey of a criminal case through the court system.

While arrest might kick off the process, it is arraignment that sets a case on its path. It’s where a defendant is formally charged. It’s also the first time that person might plead guilty or not guilty.

There is a lot of paperwork to complete and boxes to check. Is there a defense lawyer? Will the defendant be released or remanded to county jail? How much is bail going to be and are there any conditions?

In Pennsylvania, arraignment is done by the lowest level of the judiciary — district judges. These judges don’t have to be lawyers. If they are 21 and have lived in the state for a year, they can take a training class and be elected to a six-year term deciding low-level civil cases and being the gatekeeper to the criminal courts.

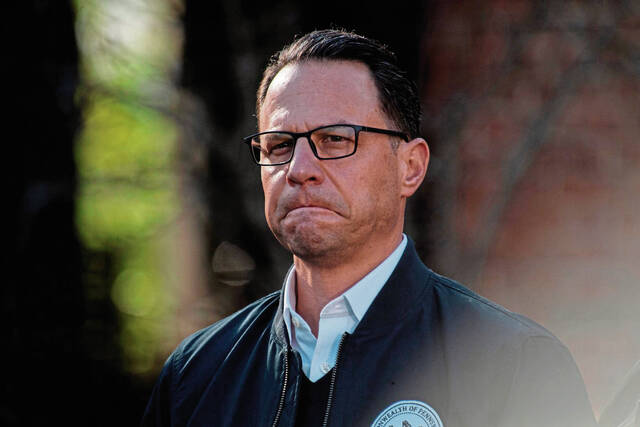

One Allegheny County district judge will no longer be presiding at arraignments.

Xander Orenstein arraigned Hermas Craddock on April 10. Craddock was charged with fleeing, assault of a law enforcement officer, firearms counts, reckless endangerment and driving under the influence. The charges stemmed from a high-speed chase. State police say he almost rammed two patrol cars and threw a gun out of the window.

When Craddock was arrested and brought before Orenstein, the district judge let the defendant go without bond, pending a preliminary hearing. Craddock did not appear in court Monday.

That’s not unusual. Plenty of defendants miss court all the time. Judiciously considered and applied bail is intended to secure that appearance. If you know you will lose your house if you skip court, you may be more likely to show up.

But bail can sometimes be applied too aggressively, becoming almost a pretrial punishment. Bail reform is an important issue that needs to be addressed. Orenstein campaigned on social justice issues, including ending the use of cash bail.

However, this is the second time that a significant case involving a person potentially dangerous to the public walked away from arraignment with little from Orenstein to compel a return to court.

On Aug. 31, Yan Carlos Pichardo Cepeda, 27, of New York was arrested at the Downtown Greyhound bus station with $1.6 million in fentanyl and a kilogram of cocaine. Orenstein released him with nonmonetary bond. Unsurprisingly, that defendant also didn’t show up for his next appearance.

Pichardo Cepeda, who was finally arrested in New York in February and is being held at Riker’s Island, had two pending cases when he appeared before Orenstein. Craddock was free on a $25,000 bond for a gun charge.

Whether by the circumstances of their arrests or their previous charges, neither defendant merited the kind of leeway Orenstein granted.

The court administration did the right thing by removing Orenstein from overseeing arraignments. The Allegheny County courts are exercising the same judicious discretion based on the judge’s actions and history that Orenstein should have exercised in at least the Pichardo Cepeda and Craddock cases.