On Jan. 7, Susan Shepherd called the police.

Her son Christopher Shepherd, 48, was in the grip of a psychiatric crisis. He had a kitchen knife. He barricaded himself in his Upper St. Clair home.

It wasn’t the first time. Christopher Shepherd was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder. Law enforcement had been called in more than a dozen times. His family was worried about him. His house was still damaged from a prior interaction.

When the mentally ill man brandished his knife, Upper St. Clair police brought in more officers. They got an arrest warrant for aggravated assault.

From that point, things escalated. Christopher Shepherd ran out with his knife. A police dog took him to the ground. The dog’s handler stepped forward to secure the animal, and Shepherd swiped at him with the knife. Then four officers fired 21 times; 18 shots hit him.

Susan Shepherd called for help for her son. When everything was over, her son was dead.

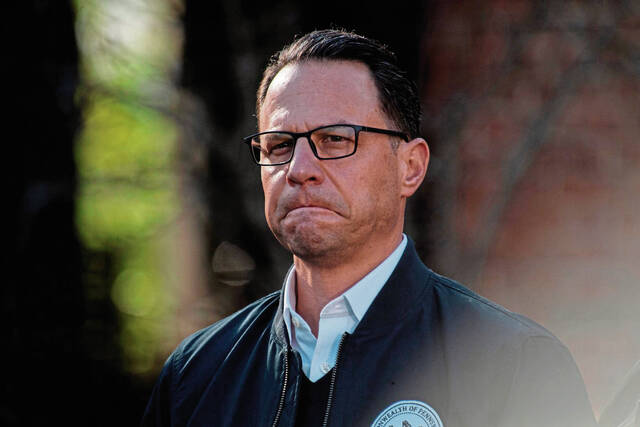

On Friday, Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala Jr. said he would not charge the four officers with Christopher Shepherd’s death.

We might ask why it took 11 months to make this announcement — and why Zappala is still not releasing the names of the officers, although they are already known. In March, the police chiefs involved submitted signed statements to the Pennsylvania Office of Open Records attesting that Zappala had determined use of lethal force was justified.

But Zappala’s slow pace toward public acknowledgment isn’t the biggest problem.

The real issue is a simple question. What should someone do when a family member or loved one has a mental health episode? How should it be handled?

Interactions between the police and the mentally ill can be dangerous on both sides. Shepherd isn’t the first person with a psychiatric diagnosis to die by an officer’s gun. In Ligonier Valley in 2023, police shot a man in similar circumstances. Pittsburgh paid out $8 million to the family of Jim Rogers, a homeless man who appeared to be experiencing mental health issues during a police interaction that ended in repeated use of a Taser.

The math shows that a significant number of officer-involved fatalities involve the mentally ill. The dead are not always the civilians. McKeesport Officer Sean Sluganski was killed in February 2023 when another man’s mother, like Sue Shepherd, called for help.

In addition, the Pew Charitable Trusts has found that those with severe to moderate mental illness and substance abuse disorders — frequent co-morbidities as patients will try to self-medicate their conditions — are 12 times more likely to be arrested.

Arrest can be a financial issue for families. It can impact the money coming into the household from paychecks or other checks. It can mean money going out for bail, lawyers, fines, etc. That could make a family wait before calling police. But the potential for that call to end in bloodshed is even more dire.

These are the stories many people talk about when they suggest reforming the way these interactions take place. Families need to feel comfortable calling for help with their loved ones. It needs to be a way to keep the patient, the relatives and the responders safe without escalating into dangerous territory.

Mental illness isn’t a crime. It’s not within the control of the diagnosed individual. It shouldn’t be treated like a willful act of defiance or aggression.

Until that changes, families will continue to risk the worst outcome when they simply call for help.