A press conference is supposed to be a give and take. Somewhere between a dance and a duel, it depends on both sides taking turns. The speaker gives a statement. A reporter asks a question. The speaker either answers or evades — which is in itself a kind of answer. The steps repeat, building off the information as it is teased out.

The process is important for a number of reasons including accessibility of the people speaking and the evolving nature of the news being released.

That is why a press conference where questions are submitted in advance is not really a press conference.

This is a public relations official’s dream. A press conference always has the possibility of an unexpected query or a bad answer. Knowing the questions ahead of time prevents that.

But it also runs counter to the point. How does a reporter know what questions to ask before information is made public? How does another reporter ask a follow-up question? How does a news agency keep a politician from wandering away from an uncomfortable topic and on to a well-rehearsed talking point?

It can’t.

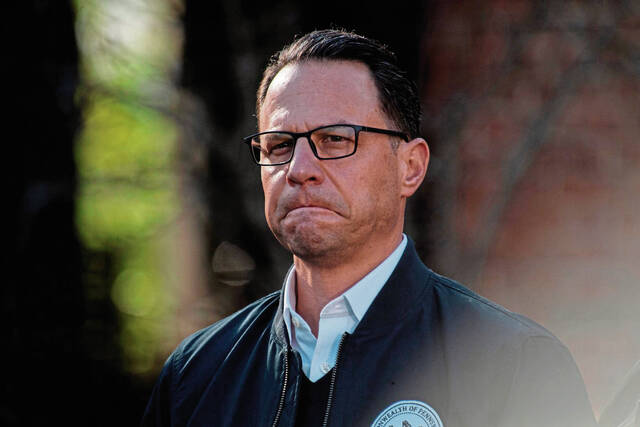

This has become a problem in the age of covid-19. In the height of the lockdowns in 2020, Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf was answering only pre-submitted questions. Politifact confirmed in February that White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki’s staff was taking questions ahead of briefings but said there was no evidence of evasion of a reporter or question.

Then there is the Allegheny County Health Department.

When Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald and Dr. Debra Bogen, department director, give their periodic updates on the pandemic and its effect on the area, they do take questions. They just don’t take them at the press conference. Questions must be submitted at least two hours ahead of time. This is noted as giving staff time to find the answers so Bogen can have the information available. That’s a good thing.

But not every question is a matter of facts that needs to be researched. Sometimes, it’s a clarification of those points, asking an expert like Bogen to break something down into more accessible explanations for the non-scientists among us. It might be pointing out a contradiction in the data. It might be as simple as “Why?”

None of that gets to happen when a reporter needs a crystal ball to know what questions need to be asked.

There may be benefits to government agencies and PR professionals when questions are submitted hours ahead of time, but that doesn’t mean it is best for the people.