A judge’s job in a courtroom is to enforce the rules as the prosecution and defense go through the steps of a trial. It is frequently less about being the hammer of judgment than it is about interpreting and enforcing the law as written by legislators and determined by years of precedent.

Except at the end.

When it comes to sentencing, a judge’s job changes. Suddenly it is less about what other people have decided about the law and more about what the judge has seen up close and personal with a defendant.

Or at least, it should be.

There is a complex arithmetic problem for sentencing that adds past history to the number of counts, multiplies by aggravating factors and divides by cooperation to come up with a recommended sum of months or years.

There is good in that. In theory, it makes things fair. Steal something worth this amount, get this many months of probation. Hurt someone in this way and face this penalty.

But it also removes the very human factor that is a judge’s role.

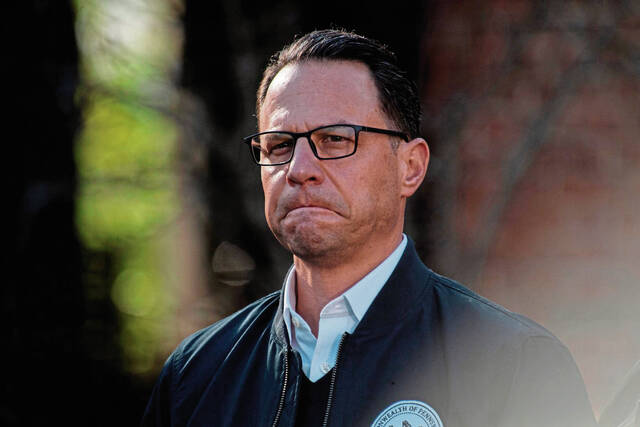

Westmoreland County Judge Christopher Feliciani brought that personal response back to the bench Friday when he sentenced an Indiana County man in a drug death. Julian Cancro, 38, will serve probation for his part in delivering the drugs that led to his girlfriend Darcie Frank’s overdose in 2019. Prosecutors sought up to 13 years in prison.

Feliciani cited Cancro’s efforts to change not only his own life but those of others who battle addiction.

“I think you probably are the early makings of Tim Phillips in our county. You can certainly step in for him when he retires,” Feliciani said.

Feliciani, who presides over Westmoreland’s drug court, would know. He has worked with Phillips — a recovered addict who is the director of the county’s drug overdose task force — for years. Phillips testified on Cancro’s behalf at sentencing.

The sentence speaks to the way courts should work — listening to all sides, considering the weight and coming to a reasoned Solomon-like solution, even if it isn’t something everyone supports. Feliciani didn’t let Cancro just walk away from responsibility. He delivered a sentence of three years on house arrest and 200 hours of community service, keeping him accountable for his actions while giving him a chance to atone.

Sentencing like this for drug-related cases is all the more important because of the role of the disease that is addiction in the crimes.

A judge is there to bring his judgment into play. Cases like this show why that human element is more important than rubber-stamping a math problem.