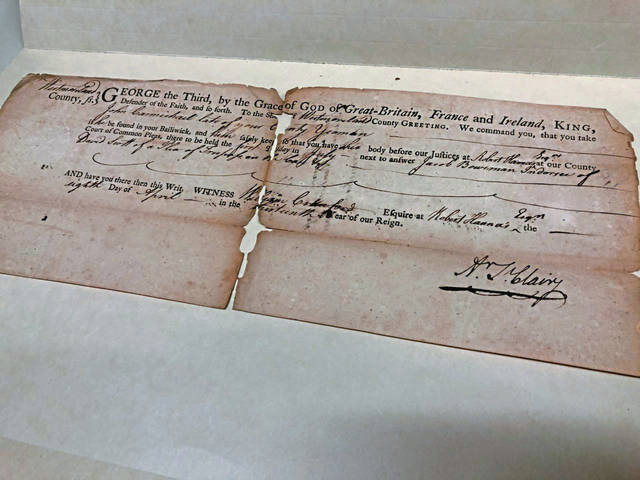

The parchment is browning in places, with the careful calligraphy stroked thinly in some spots and boldly in others. Corners and flecks of the paper are missing, chipped away like flaking paint.

The page is more than just an old letter. It is a thread in the tapestry of Pennsylvania’s history.

One of the oldest in the millions of documents maintained and stored by Westmoreland County, this one bears the signature of King George III and appoints Arthur St. Clair the county’s Recorder of Deeds. A few years later, St. Clair took up arms against that king in the American Revolution.

These are the kind of tangible links to our past that we cannot lose. They also have upkeep that becomes more expensive the older the county gets, the more documents are in the timeline and the more difficult the oldest relics become to preserve.

Sixty percent of the county’s records are at the courthouse. These would be the ones most likely to be accessed, the ones that would need to be at hand if someone came in for a receipt or a certificate. The records of property from a time when ownership of human beings was treated like possession of houses or horses are among the other 40% — the stuff stored off-site.

State law requires these shreds of history be preserved. Counties and other government agencies must retain public documents, including things like court files and tax records.

That’s a smart move for many reasons. Anyone who has been audited knows the document you are most likely to need for some down-the-road official purpose is the one you can’t find. Many a modern-day property dispute has sent people scuttling back to original paperwork.

But there is a much less concrete — but perhaps more important — reason to keep King George’s John Hancock around.

We need to remember where we came from and how we got here.

The documents stored in 32,000 or so boxes plus microfilm and digital files are a timeline we can follow back to our earliest days. We can see what we did right and what we did wrong. We can see what we thought was fine, like slavery, and how we changed our stand and when we drew a line in the sand.

Because, as the saying goes, the history we do not learn, we are doomed to repeat. The millions of pages in Westmoreland County custody can be part of holding those past mistakes at bay.